by Stephen Shafer

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] may need to go into hiding after publicly declaring the following in a forum dedicated to celebrating Madness’ illustrious career, as well as their brand new album Oui Oui Si Si Ja Ja Da Da, but back in my teen years, of all the 2 Tone era bands, I ranked Madness pretty low on my list.

For the record, here were the standings circa 1983/84:

1) The Specials/The Special AKA

2) The English Beat

3) The Selecter

4) Madness

5) Bad Manners

Before you go all Frankenstein on me and break out the pitchforks and torches for my heresy, please let me explain how I arrived at this hierarchy (and trust that later in this article I might actually redeem myself). Back when I was a teen, it was extraordinarily important to me what a band was singing about; lyrics mattered (this was, no doubt, due to the fact that during my middle school years, I was a boy chorister at an Anglican church, so I was familiar with lyrics that were ripe with religious, liturgical, and historical significance—so my expectation was that what you sang about should have meaning).

Raised by very socially/politically progressive parents (who taught me the protest songs of the Civil Rights Movement and exposed me to records like Free to Be, You and Me), I was naturally drawn to one of the most admirable aspects of 2 Tone—the propensity of the bands to speak out against injustice through their lyrics. Songs by The Beat, The Specials, and The Selecter addressed some heady issues in the Cold War-Reagan/Thatcher era that mirrored many of my own concerns about the world around me: racism and racial violence (“Racist Friend,” “Why?,” “Two Swords,” “Bristol and Miami”); the alienation, anger, aimlessness, and boredom that resulted from government policies that ignored the plight of the poor, unemployed, youth, and non-white peoples–and offered no viable way forward in life (“Ghost Town,” “Friday Night, Saturday Morning,” “Blank Expression,” “Stand Down Margaret,” “Click Click,” “Do Nothing,” “Too Much Pressure,” “Washed Up and Left for Dead”); Cold War paranoia/fear of world-wide nuclear annihilation (“Man at the C&A,” “Dreamhome in NZ,” “Selling Out Your Future,” “Their Dream Goes On”); and just being a decent human being, whether it’s using contraception when getting it on (“Too Much Too Young”) or taking a stand against something because it’s not ethically or morally right (“It’s Up to You,” “Free Nelson Mandela,” “Doesn’t Make It Alright,” “Get a Job,” “Sugar and Stress,” “Who Likes Facing Situations”).

I needed songs that not only had killer hooks and made me want to dance, but also expressed the fears, outrage, desires, and aspirations of the times (and I supposed of my generation).

All this isn’t meant to suggest that I didn’t love Madness—I did then and still do. Yet, compared (perhaps unfairly) to most of their 2 Tone brethren, I found them to be almost too sunny in their outlook/oblivious to the troubled times (though now looking back 30 years on, I can see in my callow, ignorant youth that I completely failed to recognize Madness’ often barbwire sharp commentary on British society and working class life—see “Our House,” “Land of Hope and Glory,” and many others; despite my Anglophile fanaticism for all the New Wave/post-punk music coming out of the UK, there were some bands/releases that were so British in their references that a kid from a suburb of New York City just couldn’t quite grasp their context/subtext).

“Madness,” “One Step Beyond,” and “Night Boat to Cairo” were incredible songs that were regularly broadcast into my bedroom by the local modern rock/New Wave radio station WLIR (and were a vital part of the soundtrack of my youth), but what did they have to do a cruel, chaotic world that seemed on the edge of the abyss? (Yes, it really did feel like “Armagideon Time” in the early 1980s—I actually lost sleep on many nights worrying if Russian ICBMs would rain down on us and everything would be vaporized in a flash before morning’s light.) It felt like it was a lost opportunity—not to preach—but to speak out against (and raise awareness about, even spur action to deal with) the host of issues that seemed poised to undermine, even obliterate civilization itself. (And here we are three decades later, none the wiser, dealing with much of the same crap.)

The 1983 U.S.-only compilation Madness (a mish-mash of The Rise and Fall and several previously released singles, like “House of Fun” and “Night Boat to Cairo,” that was a big seller due to “Our House,” which reached #7 on Billboard charts) was the first record of theirs that I owned, but by this stage of the game, the band’s pop quotient far outweighed its ska–and after picking up the magnificent One Step Beyond…, I pretty much lost their thread.

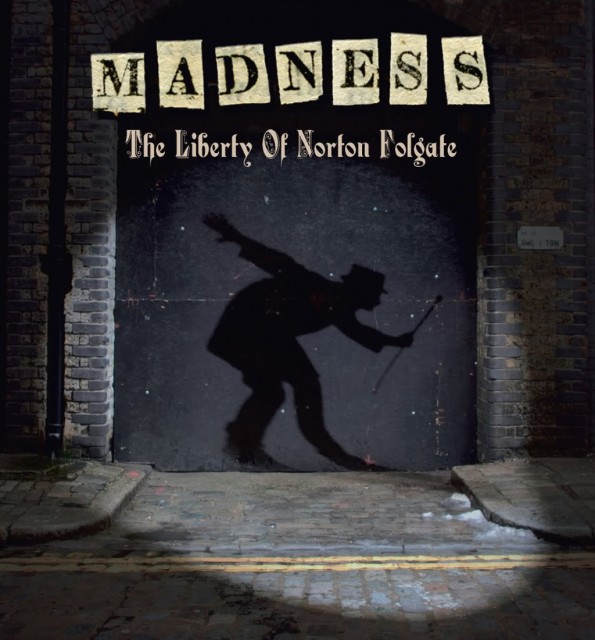

Flash forward years later to 2009—past the ska boom and bust of 1990s in America, and its phoenix-like rise again in the new millennium—to a brand new album from a re-formed Madness: The Liberty of Norton Folgate. This in itself was exceptional, as at the time all of the other major 2 Tone bands were back in action (though somewhat fragmented, with a Dammers-less Specials and two versions of The English Beat and The Selecter roaming the land) and appeared to be satisfied with simply bashing out their hits–of almost three decades ago–on the lucrative nostalgia circuit. Madness was the only band from the class of ’79 to have the decency to show up for the 30th anniversary festivities with new material in hand. There was no coasting on their collective laurels here (this from a band of middle-aged pop superstars that have sold more than 6 million singles, spent a cumulative 214 weeks in the UK singles charts in the 1980s, and command nearly universal fandom—who could have easily turned in a retread that probably would have been a smash).

While it seemed like their 2 Tone peers had run out of things to say, Madness were delivering the songs of great meaning that I had wanted from them in my youth—a concept album that promotes/embraces multiculturalism as the only path to real freedom, and the notion that the history of a place and its people has an extraordinary impact on making this possible.

While the whole album is stellar, I want to highlight “We Are London” and “The Liberty of Norton Folgate”—the songs that bookend the album.

“We Are London” is the album’s thesis:

“From Regents Park mosque onto Baker Street

Down to the Cross where all the pipes

smoke neat

To Somers Town where some things never stop

The Roundhouse, The Marathon bar

in Camden lock

You can make it your own hell or heaven

Live as you please

Can we make it if we all live together

As one big family

Down to Chinatown for duck and rice

Along old Compton Street the boys are nice

On Carnaby you still can get the threads

If you wanna be a mod, a punk, a ted

or a suede head

You can make it your own hell or heaven

Live as you please

Can we make it if we all live together

As one big family

In all the nightclubs, strip joints and the bars

From its poorest paid to its highest stars

The poets, plumbers, painters spreads and sparks

From its inner city to its furthest parts

You can make it your own hell or heaven

Live as you please

Can we make it if we all live together

As one big family

We are London

London talking

We are London

London walking”

This isn’t the stereotypical call for racial unity from a ska band—it’s pointing out and celebrating the vital opportunity that diverse, cosmopolitan cities like London or New York offer all of us: to “live as you please.” This is only possible because so many people of all colors, nationalities, viewpoints, classes, and creeds have been drawn to this urban setting–living, playing, and working in such close quarters. Difference, tolerance, and freedom are the established norm here.

Just as New York City’s incredible diversity and social/political liberal traditions came about due to the fact that she was the point of entry for successive waves of immigrants for decades, the liberty that people enjoyed for centuries in Norton Folgate is due to the history of its unique geographical place.

The Liberty of Norton Folgate is, as Suggs writes in his extensive liner notes for the album, “a travel song in one place…about one small area of London—gets the x-ray camera out and shoots down through the crust, past the bullets and bones, the clay pipes and stones to try and get to the soul of the place.” It focuses on an area that sprang up outside the old London city walls (originally a garbage dump) in the 1100s that first served as a point of entry for immigrants and outsiders. It eventually developed into an unofficial town with its own laws and conventions apart from those of London proper. By the 1700s, London had encompassed Norton Folgate, but it remained independent of London (hence, “the liberty of”), run by a group of trustees, and was home to generations of immigrants, as well as a “refuge for actors, writers, thinkers, louts, lowlifes and libertines, outsiders and troublemakers all,” in Suggs’ words.

Norton Folgate was a place that fostered freedom, diversity, and tolerance despite—or more likely because—its reputation as a place of ill repute. It was society’s receptacle for outsiders. And at that point proper London society couldn’t be bothered with enforcing its conventions on Norton Folgate’s citizens. This is what fascinated Suggs and the band—that “certain areas seem to retain their distinct personality through centuries of time and the passing of generations’ different peoples.”

In the epic “The Liberty of Norton Folgate,” a walk through the street’s stalls with its small businesspeople hawking their wares (“There’s a Chinese man trying hard to flog you moody DVDs”) is a walk through Norton Folgate’s history: “A continual dark river of people/In their transience and in its permanence.”

As Suggs is “Purposefully walking nowhere/Oh I’m happy just floating about (have a banana)/On a Sunday afternoon/The stall holders all call and shout (to no-one in particular)/Avoiding people you know,” he imagines what had happened on that very spot centuries ago (i.e., occupying the same place, but in a different time, a la H.G. Welles’ Time Machine):

“Sailors from Africa, China and the Archipelago of Malay

Jump ship ragged and penniless into Shadwell’s Tiger Bay

The Welsh and Irish Wagtails – mothers of midnight

The music hall carousal is spilling out into bonfire light

Sending half crazed shadows, giants

Dancing up the brick wall

Of Mr. Truman’s beer factory

Waving bottles ten feet tall

Whether one calls it Spitalfields, Whitechapel,

Tower Hamlets or Bangle Town

We’re all dancing in the moonlight

We’re all on borrowed ground”

And then he goes back further in time to the origins of Norton Folgate—its creation story:

“In the beginning was fear of the immigrant

In the beginning was the fear of the immigrant

He’s made his way down to the dark riverside

They made their home there down by the riverside

They made their homes there down by the riverside

The city sprang up from the dark mud of the Thames”

The song’s chorus brings home the message—the current presence of freedom is due to its past people and the enduring existence of the place. And the location’s ongoing freedom is fostered—kept alive, really—by the people who continue to be aware of and enjoy this liberty:

“‘Cos in the Liberty of Norton Folgate

Walking wild and free

And in your second hand coat

Happy just to float

In this little taste of liberty

‘Cos you’re a part of everything you see

Yes, you’re a part of everything you see”

At the time of The Liberty of Norton Folgate’s release, I devoted a considerable amount of space to highlighting other writer’s reviews of the album from the mainstream music press. I started—and struggled with—putting together a lengthy review of Norton Folgate. But the ideas threaded throughout the album were so big and complex, I felt that I couldn’t accurately and fully represent them (and, to be honest, I don’t think any of the other reviews I read ever did!). So this essay is a means to finally pay tribute to Madness’ brilliant and masterful collection of songs—and to publicly work through my reappraisal of Madness from a music geek’s point of view.

Hopefully, you’ve a) made it this far in my meandering appreciation, and b) aren’t still gunning for me because of my youthful, three decades-old opinion of Madness. With The Liberty of Norton Folgate, Madness beautifully uphold and honor the 2 Tone ethos and, in this writer’s most humble opinion, definitely have something meaningful (and then some!) to say.

[alert type=”blue”]This post is part of the Madness Album Series at REGGAE STEADY SKA. To celebrate the arrival of Madness’ tenth studio album “Oui Oui, Si Si, Ja Ja, Da Da”, we asked Madness lovers from around the world for their personal tales on Madness and their albums. For an overview on all the texts from this series, please go here. Album No. 9, “The Liberty Of Norton Folgate”, was released in 2009.

[/alert]

I agree – their best yet……………………………….

Great article! I think this is the best Madness album alongside One Step Beyond